Renaissance-era scholar Machiavelli's impact on academic culture and the growth of private study rooms during the Renaissance period

In the rolling hills south of Florence, nestled among vineyards and olive groves, lies the quaint town of Sant'Andrea in Percussina. It was here, in the summer of 1513, that a disgraced and forty-four-year-old Niccolo Machiavelli sought refuge following his dismissal from a lofty post and a trial for conspiracy.

Machiavelli's retreat was not just a physical escape but a sanctuary for reflection, study, and the collection of knowledge. His study, or studiolo, became a symbol of the Renaissance intellectual's dedication to learning, strategy, and the arts.

For Machiavelli, his studiolo was more than just a room. It was a representation of his inner intellectual life, where careful observation, critical thought, and the study of history merged, leading to his seminal works like "De principatibus," better known as "The Prince."

In the tradition of the Renaissance, the studiolo was a treasure trove of art, science, and philosophy, reflecting the era's humanist ideals. Machiavelli's studiolo symbolised the intersection of practical politics and learned culture, crucial to his life’s work of advising rulers on governance and power dynamics.

While there are no direct visual or detailed descriptions of Machiavelli’s personal studiolo in the records, the broader Renaissance tradition of studioli and their role in fostering intellectual creation and statecraft clearly contextualises its significance in Machiavelli’s career and writings.

The enclosure of the study offered a paradoxical sort of freedom, a conceptual pharmakon, a cure or poison for the soul. It provided Machiavelli with the space to delve into his thoughts, away from the bustle of the world, and to synthesise classical knowledge and contemporary political realities.

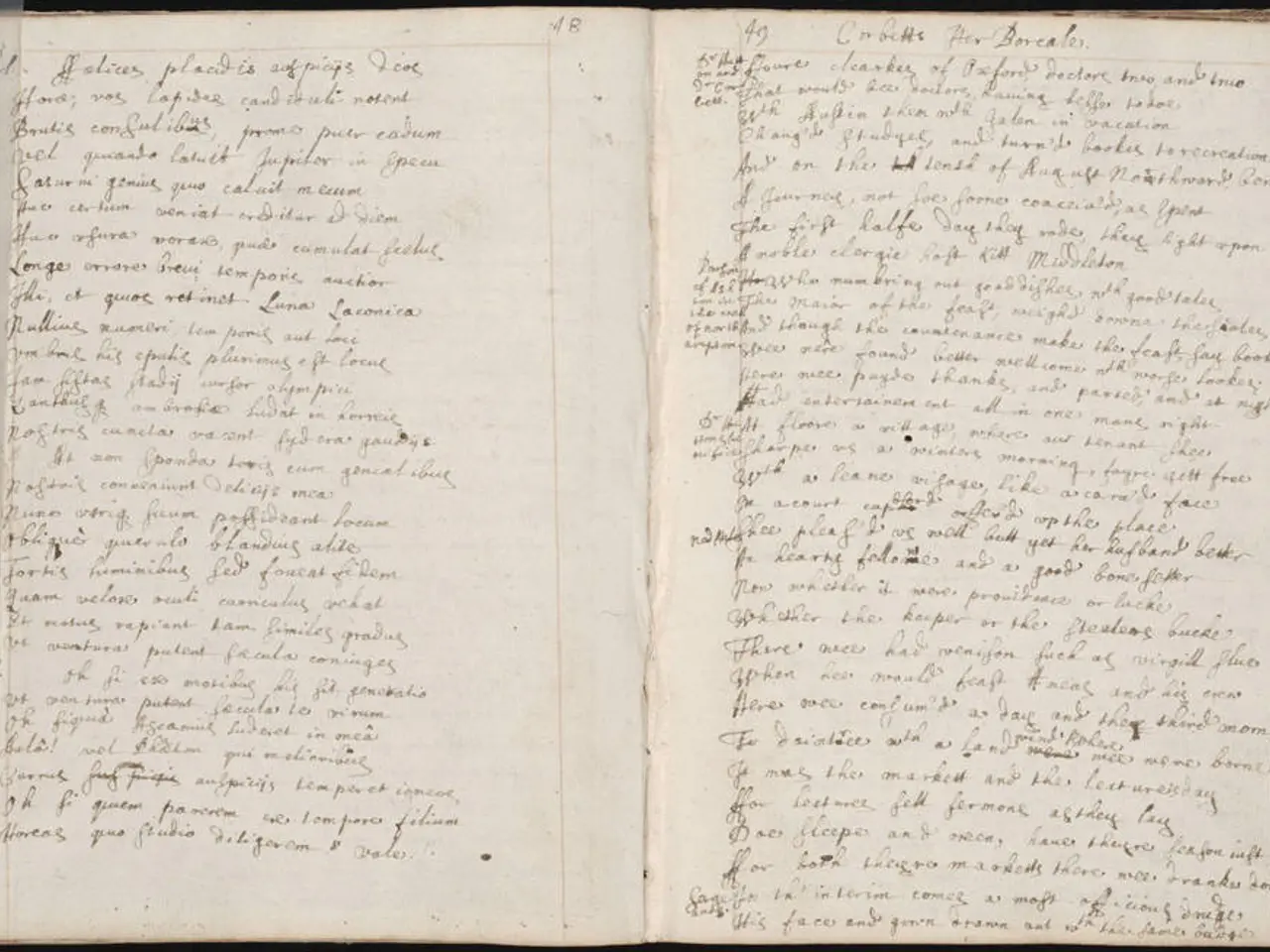

Machiavelli's letters to his friend Francesco Vettori, exchanged between 1513 and 1515, offer a glimpse into his life during this period. In one of his letters, dated December 10, Machiavelli describes his imaginary library where he converses with ancient authors. In another, he describes a typical day of his own: he spends his mornings trapping birds or cutting down trees, plays card games with local villagers in the afternoon, and reads Dante, Petrarch, Tibullus, or Ovid in the evenings.

The studiolo was not just a solitary space but a place where Machiavelli felt no boredom, forgot his troubles, and was not terrified by death. It was a paradoxical sanctuary, a place of intellectual freedom amidst physical isolation.

In contrast, Michel de Montaigne, a contemporary of Machiavelli, saw solitude as a necessity for true liberty. In his essay "Of Solitude," he discusses the need for a "back room" for real liberty and principal retreat and solitude, evoking a shophouse bustling with trade rather than the tranquility of a nobleman's secluded estate.

For Montaigne, there was a continuum between interior spaces, intellectual interiority, and spiritual inwardness. The built environment not only enclosed his body but also reflected his inner life. His library tower had inscriptions of ancient maxims and biblical proverbs on the ceiling beams, forming a sort of architectural commonplace book.

The Christian tradition posits that reading is a dialogue with God, but for Machiavelli and others, reading became a dialogue with the voices of antiquity. This shift in perspective, from a divine to a human conversation, marked a significant departure from the religious undertones of the Middle Ages and ushered in the age of humanism.

In the footsteps of Petrarch, who constructed a small villa with a study, one of the first to do so unattached to any institutions, Machiavelli and other Renaissance thinkers recognised the importance of a dedicated space for study and reflection. This space, the studiolo, became a must-have accessory for the aristocrat and humanist alike in the 1500s.

However, the studiolo may promise a false abundance, becoming a closed system that seals itself up into a mirror-house of solipsism. W. E. B. Du Bois, in "The Souls of Black Folk" (1903), evoked a similar sentiment when he spoke of his conversations with authors—dead and white—finding in books a transhistorical humanity that offered him horizons of thinking beyond the limits of segregation and bigotry.

In conclusion, Machiavelli's studiolo was more than just a room. It was a symbol of the Renaissance intellectual's pursuit of knowledge, a sanctuary for reflection and a laboratory for ideas. It was a place where the past and the present converged, and where the seeds of modern political thought were sown.

Books filled the studiolo, serving as a bridge between Machiavelli's personal growth and education-and-self-development. They were not just a source of entertainment but a reflection of his intellectual life, intertwining critical thought, history, and strategy.

In this sanctuary of knowledge, Machiavelli found himself in a continued dialogue with ancient authors, using books as a medium for personal growth and the shaping of modern political thought.